The Impact of the Opioid Crisis on Tribal Communities

By Michele L. Scott, M.S., Gretchen Vaughn, Ph.D., and Setu K. Vora, M.D.

How do we aim that arrow on a moving target?

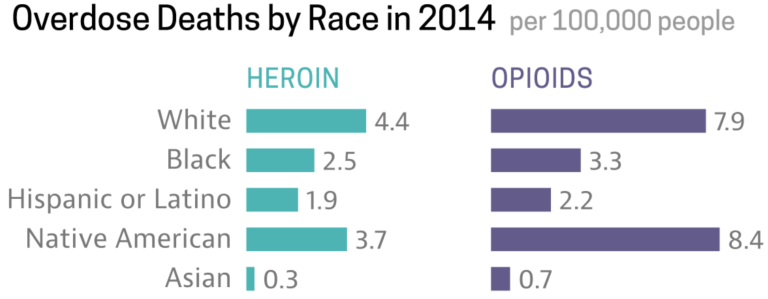

The opioid crisis in the United States has had a severe and chronic impact on American Indian/Alaskan Native (AI/AN) communities. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, documented that AI/AN communities had the highest drug overdose death rate in 2015 and that this rate had grown 519% between 1999 and 2015 (Mack, Jones, & Ballesteros, 2017). According to Rear Admiral Michael Toedt, the medical director of the Indian Health Service, this was “the largest percentage increase in the number of deaths over time…. compared to other racial and ethnic groups…[and] may be underestimated by up to 35 percent.” (Toedt, 2018). The impact on AI/AN communities compared to other ethnic groups is illustrated in a 2014 CDC graphic showing the opioid overdose rate for Native Americans (8.4 per 100,000) was higher than for any other racial group, and the heroin overdose rate was also disturbingly high (3.7 per 100,000) (NCAI, 2016).

Prior to the national and widespread efforts to combat the opioid crisis, tribal communities started to identify, name, and address the growing epidemic. The alarm was first raised about the impact on youth in a 2011 CDC Vital Signs report that found 1 in 10 AI/AN youths age 12 or older used prescription opioids for nonmedical reasons, compared to 1 in 12 non-Hispanic white and 1 in 30 African American youths (CDC, 2011). Additionally, rates of heroin and Oxycontin use were higher among AI/AN adolescents who live on or near reservations, and the rates of neonatal opioid withdrawal among the AI/AN population were higher in some communities (NCAI, 2017).

This problem is being addressed within very diverse tribal communities both rural and urban, from many regions of the country with a variety of historical, social, and cultural determinants that impact tribal health. Additionally, this crisis involves regional supply and demand of both prescription opioids (natural: e.g., morphine; semi-synthetic: e.g., oxycodone; synthetic: e.g., tramadol) and illegal opioids (heroin; illicitly manufactured fentanyl).

These complex issues are often exacerbated by tribal communities’ historical relationship with Western medicine. “AI/AN communities are doubly impacted when opioids are overprescribed in place of appropriate healthcare” (NCAI, 2017). There is a serious need for more of local and tribal level data, for collaboration across multiple departments and service sectors, and access to prevention and treatment funds. Despite these clear barriers, sovereign Tribal Nations and tribal organizations have unique resources and opportunities to respond to this crisis “in a good way,” integrating cultural healing practices with evidence-based strategies. With additional resources and an acknowledgment of this crisis, tribal communities’ cultural healing strategies can be equally valued with mainstream evidence-based strategies.

Understanding opioid use in AI/AN communities means acknowledging the historical trauma or “cumulative emotional and psychological wounding, over the lifespan and across generations, emanating from massive group trauma experiences” (Brave Heart, 2003). AI/AN communities have experienced historical trauma in many forms over the years and this trauma persists today in the form of economic inequality, loss of culture, and discrimination. “The resulting trauma is often transmitted from one generation to the next” (SAMHSA, 2014). Historical trauma response is a constellation of features in reaction to massive group trauma that may include a level of unresolved grief and anger that contribute to physical and behavioral health disorders on both individual and community levels (Brave Heart, 2003). To understand the context in which the opioid crisis arose in Indian Country, it is important to recognize that tribal cultural practices have always been and can continue to be the principal source of healing. “Healing practices should acknowledge the root causes of intergenerational and other types of trauma…” (TBHA, 2016). Oré et. al., in a recent literature review of AI/AN resilience found that it was accessed through cultural knowledge and practice (Oré, 2016). “In the face of these inequities, many AI/AN individuals and communities continue to resist, to be resilient and to thrive (Ore, 2016). “We know that Native American wisdom exists within our stories, language, ceremonies, songs, and teachings. We know our Native ways are effective” (TBHA, 2016).

Tribal communities have responded to this crisis with several priority goals in mind:

- Culture and tribal sovereignty as the core of any action

- Prevention of opioid misuse and abuse

- Expansion of prevention services in education, recreation, and community support

- Expansion of access to opioid use disorder treatment

- Prevention of deaths from overdose.

In 2018, the National Indian Health Board recommended three policies to address the opioid epidemic in AI/AN communities:

- Establish a tribally specific funding stream on the state and federal level;

- Establish trauma-informed interventions to reduce the burden of substance misuse disorders; and

- Establish special behavioral health programs that model the existing structures of already-established successful programs in Indian Country, e.g., Special Diabetes Program for Indians.

The National Tribal Behavioral Health Agenda (TBHA, 2016) recommends using a framework that addresses each tribal community’s unique behavioral health issues. The use of this framework organized around five foundational elements reflects that fact that there is no single strategy for the complex undertaking of improving the behavioral health of diverse AI/AN populations.

- The magnified impact of historical and intergenerational trauma for tribal communities “requires practice-based actions” to support healing. This priority area focuses on “creating viable and appropriate support mechanisms, promoting community connectedness and breaking the cycle of trauma.” (TBHA, 2016)

- Developing a higher level of national awareness and visibility about the AI/AN behavioral health disparities that underlie substance use, physical health, and well-being. This priority focuses on increasing visibility of behavioral health issues while ensuring that “Tribal governments have the ability to control the messages…”(TBHA, 2016)

- Using a social-ecological approach that captures the larger context within which AI/AN behavioral health issues are rooted. This priority area focuses on “sustaining environmental resources, ensuring reliable infrastructure, and supporting healthy families and kinship.” (TBHA, 2016)

- Providing prevention and recovery support that uses traditional AI/AN integrated mind, body, and spirit healing practices. This priority area focuses on “restructuring programming to meet community needs and advance community mobilization and engagement.” (TBHA, 2016)

- Addressing the need for coordination, linkages, and expanded access through behavioral health service and system improvement that addresses workforce shortages and limited local healthcare resources. This priority area creates opportunities for collaboration of prevention, treatment, and services. It also promotes community and leadership to drive real action.

The National Congress of American Indians recently outlined specific actions steps and cross-sector opportunities (NCAI, 2018).

- Providers – pain management education, drug prescribing guidelines, drug monitoring programs

- Pharmacy – education/counseling patients on proper use, potential for abuse, security measures to prevent diversion, double signatures for dispensing

- Identification and treatment for impaired providers

- Increased access to specialty care, referral funding for conditions requiring pain management

- Better diagnosis of addiction, access to treatment/recovery services, inpatient/outpatient treatment, medication-assisted therapy, naloxone use

- Strategies to address root causes: trauma, chronic stress, mental health counseling/treatment

- Additional funding for grants to communities for interventions

- Education and treatment guidelines for neonatal abstinence syndrome

- Enhanced arrest/convention of drug trafficking, diversion, theft, illegal manufacturing

- Drug court options for addicts instead of jail/prison time

- Increased access to treatment/recovery services for the incarcerated

- Law enforcement strategies

- Community opioid emergency declaration

- Community needs assessment, strategic planning, collaboration with other stakeholders

- Community awareness, education, wellness, and prevention activities

- Naloxone distribution

- Community economic development strategies

- Implementation of the recommendations of the Tribal Behavioral Health Agenda Community strategies

- Pharmaceutical company oversupply – seek economic and injunctive relief to prevent future abuses

- Education and awareness of opioid crisis, available resources, collaboration with tribes

- More data/research on needs, solutions, sharing of best and promising practices

- Increased resources for provider, treatment/recovery, law enforcement and community strategies

These strategies can be useful throughout Indian Country, but tribal communities must choose what is most appropriate and effective for their people. Across the United States, tribes have approached the ongoing opioid epidemic differently. For example, in Maine four Tribal Nations (Passamaquoddy, Micmac, Penobscot, and Wabanaki) were awarded project-specific funding through the Department of Health and Human Services to combat substance abuse and for community health initiatives. The funding targets barriers such as aftercare services, medication-assisted treatment (MAT), and increasing clinician capacity. Their neighbors to the south in Connecticut, the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation (MPTN), have committed to another approach that has integrated prevention and opioid treatment throughout the community for the past five years.

The first step for this tribal community was to recognize and acknowledge the problem on all levels, from political leadership to community adult members to youth council. A tribal member led community forums and talking circles where the MPTN community was invested in inclusive dialogue to design solutions that came from within. The feedback collected from the initiative was organized and returned to the community to develop subcommittees and action plans. The need to overcome the opioid crisis with both cultural healing and evidence-based strategies was a consistent theme. A group comprising tribal leaders, behavioral health champions, consumers, elders, and youth formed the project MPTN Opioid Use Taskforce (MPTN-OUT) and formulated the following action steps using a business model canvas to outline desirable, feasible, and viable goals.

- MPTN-OUT will build an opioid use disorder (OUD) prevention program based on a strategic plan to identify service gaps and reduce harm for the high-risk segment of the target population.

- MPTN-OUT will establish a standing order protocol to authorize any pharmacist practicing in MPTN to dispense naloxone to people who are at risk or to people around those at risk of opioid overdose.

- MPTN-OUT will build an evidence-based, systems-based model to provide Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) to people suffering from OUD with collaboration between Tribal Health Services and regional Opioid Treatment Program.

- MPTN Tribal Health Service will have at least a part-time nurse practitioner with appropriate waiver license to prescribe buprenorphine.

- All the staff at Tribal Health Services will complete the OUD training module offered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to ensure that individuals working in tribal communities are well versed in strategies to prevent and treat opioid misuse. A nurse care manager/social worker will be identified and trained to perform the “Glue Person/Care Partner” role of patient triage, counseling, and care coordination with a prescriber, local behavioral health service, and partnering opioid treatment program to facilitate ongoing medical and OUD management.

- MPTN-OUT will establish a recovery support services program for tribal members and will implement community recovery support services by recruiting two recovery coaches to become certified by the Connecticut Community for Addiction Recovery. The community recovery coaches will collaborate with local MPTN Police and Fire Departments and EMS system that may respond to an overdose and may use naloxone.

- MTPN will focus on Community Connectedness from “Tribal Behavioral Health Agenda” and initiate Gathering of Native Americans events to support community healing from historical trauma and enhance local prevention capacity through meaningful activities that incorporate healthy traditions; focus on a holistic approach to wellness; empower community members; and provide a safe place to share, heal, and plan for action.

The following resources may be helpful for providers and communities in their efforts to reduce misuse and overdose in AI/AN populations.

- Bingham, K., Cooper, T., & Hough, L. (2016). Fighting the Opioid Crisis: An ecosystem approach to a wicked problem. Report from the Deloitte Center for Government Insights, Deloitte University Press. Downloaded October 30, 2018.

- Bureau of Justice Assistance Law Enforcement Naloxone Toolkit website

- CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain resource page

- CDC Rural Health website

- SAMHSA's Opiod Overdoes Prevention Toolkit

- SAMHSA’s Opioid Overdose Toolkit flyer

- The Indian Health Service (IHS) National Committee on Heroin, Opioids, and Pain Efforts (HOPE) recently launched a HOPE committee website to share information with key stakeholder across Indian Country.

- The National Tribal Behavioral Health Agenda, December 2016. A collaborative tribal-federal blueprint for improving the behavioral health of American Indians and Alaska Natives.

- National Congress of American Indians Policy Research Center website

- Rural Health Information Hub’s toolkit, which provides evidence-based examples, promising models, program best practices, and resources that can be used to implement substance abuse prevention and treatment programs.

- SAMHSA's webpage on American Indian and Alaska Native: Tribal Affairs

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services resource of tools and information for families, healthcare providers, law enforcement, and other stakeholders about prescription drug abuse and heroin use prevention, treatment, and response.

Brave Heart, M. Y. (2003). The historical trauma response among Natives and its relationship with substance abuse: A Lakota illustration. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 35(1), p. 7.

CDC (2011). Vital Signs: Prescription Painkiller Overdoses in the US. November 2011. National Center of Injury Prevention and Control.

Mack, K., Jones, C., & Ballesteros, M. (2017). Illicit Drug Use, Illicit Drug Use Disorders, and Drug Overdose Deaths in Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Areas – United States. MMWR Surveill Summ 2017;66(No. SS-19):[1-12]. Downloaded October 19, 2018.

NCAI Policy Research Center (2016). Research Policy Update: Reflecting on a Crisis: Curbing Opioid Abuse in Communities. National Congress of American Indians, October 2016.

NCAI Policy Research Center (2018). Research Policy Update: The Opioid Epidemic: Definitions, Data, and Solutions. National Congress of American Indians, March 2018.

Oré, C.E., Teufel-Shone, N.I., & Chico-Jarillo, T.M. (2016). American Indian and Alaska Native Resilience Along the Life Course and Across Generations: A Literature Review. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2016; 23(3): 134-157.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Toedt, M. (2018). Statement before the Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate Oversight Hearing “Opioids in Indian Country: Beyond the Crisis to Healing the Community.” March 14, 2018.

TBHA (2016). The National Tribal Behavioral Health Agenda. December 2016. Department of Health and Human Services, SAMHSA, IHS, & Indian Health Board. Pub. ID. PEP16-NTBH-AGENDA